Theme:

Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest and most resource-rich province, has long been portrayed as a victim of federal neglect and oppressive central policies. However, this narrative oversimplifies the region’s complex reality. While Islamabad’s missteps are undeniable, the deeper, often overlooked crisis lies within Balochistan itself—rooted in decades of corruption, political manipulation, and betrayal by its own tribal and political elites. Entrenched in feudal power structures, these leaders have consistently diverted public funds, sabotaged development projects, and nurtured militancy to preserve their personal influence.

The consequences are severe: persistent underdevelopment, widespread poverty, disillusioned youth, and a toxic cycle of violence that has delegitimized state efforts and stunted genuine progress. Despite constitutional amendments and mega-investments like CPEC, the province remains stuck in a web of exploitation spun not just by the state but by those claiming to defend it.

This article aims to reframe the discourse by exposing how internal corruption and elite opportunism have fueled Balochistan’s instability more than any external force. By bringing this uncomfortable truth to light, it seeks to shift the conversation from grievance politics to accountability and structural reform—toward a Balochistan that serves its people rather than its powerbrokers.

Aim:

To expose the internal corruption and opportunism of Balochistan’s leadership as a primary cause of the province’s chronic instability and underdevelopment.

Scope:

This article critiques the dominant narrative of state oppression in Balochistan by focusing on how local political and tribal elites have misappropriated public funds, manipulated militancy, and obstructed progress for personal gain. It draws on historical context, financial scandals, political figures, and case studies to present a detailed examination of the province’s internal dysfunction.

Betrayed Trust:

The narrative of Baloch discontent in Balochistan’s grievances has long been framed as a struggle against state neglect. However, a closer examination reveals a more insidious truth: decades of systemic corruption, mismanagement, and duplicity by Balochistan’s political elite have fueled the province’s instability.

While the Pakistani government has allocated substantial resources to uplift Balochistan, its leaders, entrenched in feudal power structures, have repeatedly siphoned funds meant for public welfare to enrich themselves, suppress dissent, and even arm anti-state militias. The result is a tragic cycle of poverty, radicalisation, and distrust that harms ordinary Baloch citizens the most.

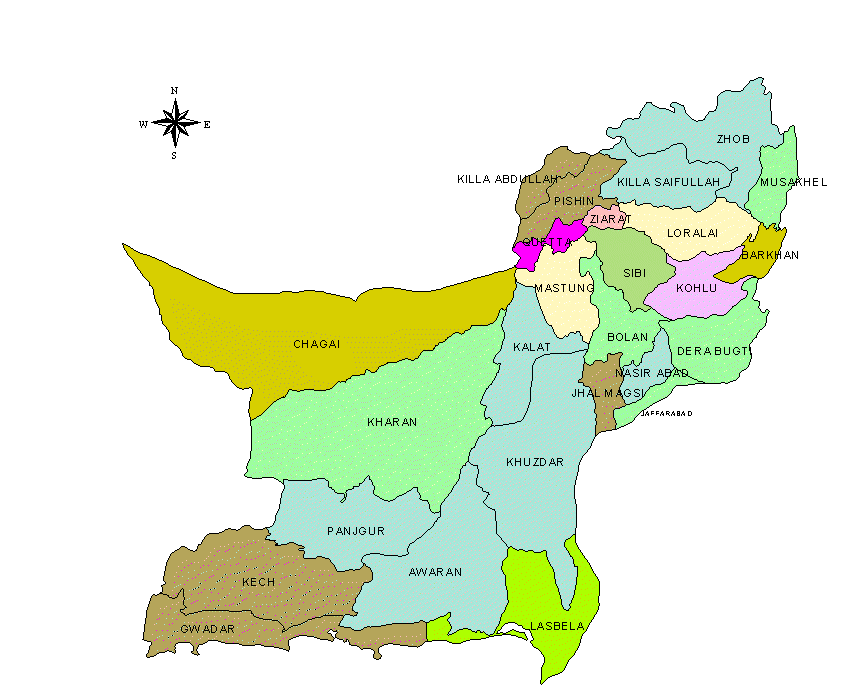

The insurgency in Balochistan is an ongoing insurgency[41][16] and revolt[42] by Baloch separatist insurgents and various Islamist militant groups against the Government of Pakistan and Iran in the province of Balochistan. Rich in natural resources, Balochistan is the largest, least populated and least developed province in Pakistan.[43] Armed groups demand greater control of the province’s natural resources and political autonomy.[44]

Baloch separatists have attacked civilians from other ethnicities throughout the province.[45] In the 2010s, attacks against the Shia community by sectarian groups, though not always directly related to the political struggle, rose, contributing to tensions in Balochistan.[46][47] In Pakistan, the ethnic separatist insurgency is low-scale but ongoing mainly in southern Balochistan, as well as sectarian and religiously motivated militancy concentrated mainly in northern and central Balochistan.[48]

A History of Broken Promises

Where did the money go?

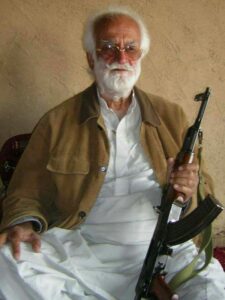

Feudal Lords Turned Warlords

Other prominent families, such as the Mengals and Marris, have similarly exploited state resources. Sardar Akhtar Mengal, a former chief minister and head of the Balochistan National Party (BNP), has long criticised Islamabad for “oppression,” yet his tenure saw little improvement in governance.

Militias: A Business Model for Elites

The CPEC Paradox: Elites vs. Progress

Accountability: The Path Forward

Final Word:

Balochistan’s true liberation will not come from resisting Islamabad but from breaking the chains of internal exploitation. The people deserve leaders who serve, not rule. Accountability is the first step toward healing.