Pakistan’s Emergence and East Pakistan’s Struggle: Leaders, Challenges, and the Road to Separation

Pakistan’s Emergence and East Pakistan’s Struggle is a profound tale of aspiration, political struggle, and eventual division. It involves visionary leadership, the hopes and hardships of millions, and a complex interplay of internal challenges and external interferences. Central to this narrative is the critical role played by the people and leaders of East Pakistan, whose contributions, grievances, and resilience shaped the destiny of the subcontinent in the mid-20th century.

https://mrpo.pk/independence-day-pakistans-journey/

The Emergence of Pakistan: A Nation Conceived in Complexity

Pakistan came into being in 1947 as a homeland for Muslims in British India, born from decades of agitation for political rights. The vision was to create a united nation where Muslims could live with political freedom and cultural respect. However, Pakistan was geographically divided into two wings: West Pakistan (modern-day Pakistan) and East Pakistan (modern-day Bangladesh), separated by more than a thousand miles of Indian territory.

From the beginning, the unity of these two wings presented extreme challenges. The diverse linguistic, cultural, and economic fabric of East Pakistan, which housed the majority of Pakistan’s population, contrasted sharply with West Pakistan’s centralised political power and financial control.

The Leading Role of East Pakistan in Pakistan’s Formation

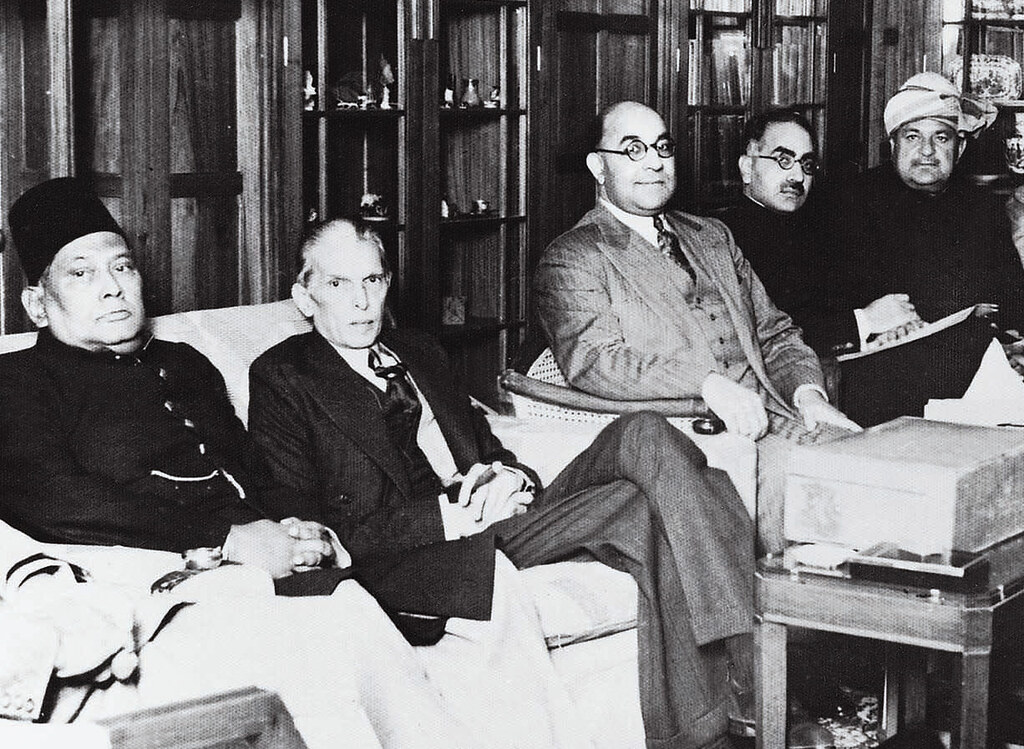

While the national narrative often highlights West Pakistani figures, the role of East Pakistani leaders and people was pivotal in Pakistan’s creation and early politics.

-

A.K. Fazlul Huq, known as Sher-e-Bangla (Tiger of Bengal), was an influential leader who shaped the political landscape by presenting the Lahore Resolution in 1940, which became the blueprint for Pakistan’s creation. Huq’s leadership included serving as the prime minister of Bengal and later prominent roles in Pakistan’s polity.

-

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a charismatic leader and political strategist, co-founded the United Front alliance that dramatically challenged West Pakistani dominance in East Bengal politics. Serving as East Bengal’s Chief Minister and later as Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Suhrawardy championed liberal democracy and East Pakistani rights.

Together, these leaders signified East Pakistan’s formidable political will and the demand for justice in the fledgling country.

General Conditions of the People of East Pakistan

Life for East Pakistanis after 1947 was marked by a mix of hope and hardship. Despite being the demographic majority, the region faced political marginalisation and economic neglect. Resources and development funds directed from Islamabad disproportionately favoured West Pakistan. This imbalance manifested in inequities in infrastructure, education, and industrial growth.

Culturally, linguistic identity became a flashpoint. The imposition of Urdu as the sole national language alienated the Bengali-speaking majority, inflaming tensions. The Bengali Language Movement of the early 1950s, demanding recognition of Bengali alongside Urdu, was met with resistance and repression, but it was a critical moment in asserting the East Pakistani identity.

The people of East Pakistan, rich in cultural heritage and economic potential, increasingly perceived themselves as second-class citizens within Pakistan.

Initial Leadership Blunders by West Pakistan

The foundational years of Pakistan were fraught with strategic and political errors that widened the gulf between East and West.

West Pakistani leadership exercised heavy-handed, centralised control, limiting East Pakistan’s political participation. One clear example was the “One Unit” policy that merged West Pakistani provinces to create parity with East Pakistan despite population differences, effectively diminishing East Pakistani influence.

Economic policies favoured West Pakistan starkly, depriving East Pakistan of its fair share of revenues, including those from its fertile lands and ports.

In leadership circles, East Pakistan was often viewed with suspicion or outright disregard, as the ruling elite in West Pakistan failed to understand or address the region’s legitimate aspirations. These missteps built deep mistrust.

The analogy often used is of two siblings sharing a room, but only one having the key to the door. East Pakistan consistently found itself locked out of power and resources.

Indian Interference: A Shadow in the Background

From the outset, India watched Pakistan’s formation warily. Historical rivalries and geopolitical tensions made India’s stance toward Pakistan cautious and, at times, adversarial.

India’s interference in East Pakistan was subtle yet impactful. Intelligence and historical accounts suggest strategies such as employing Hindu teachers in educational institutions across East Pakistan. This was not just about employment; education profoundly shapes ideology, and these teachers allegedly seeded narratives that questioned Pakistani nationalism, thereby polarising communities along religious and ethnic lines.

Further, India actively supported liberation movements by recruiting, training, and provisioning dissident groups in East Pakistan, especially as the political situation deteriorated after 1970. These covert operations bolstered separatist sentiments and armed struggle, directly influencing the course of the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War.

The Indian-sponsored infiltration of East Pakistan’s educational institutions in the years leading up to 1971 is a lesser-discussed but crucial part of the psychological groundwork for the dismemberment of Pakistan.

It wasn’t just military action in 1971; India’s strategy was long-term, working quietly in the classrooms, student unions, and academia from the 1960s onward to shape an entire generation’s perceptions.

1. The Concept of Educational Infiltration

- Indian intelligence agencies, particularly RAW (from 1968) and earlier intelligence networks, used covert agents disguised as teachers, professors, and educationists to penetrate schools, colleges, and universities in East Pakistan.

- The goal was to gradually reframe history, culture, and identity to detach Bengali youth emotionally and intellectually from the idea of a united Pakistan.

- This method was more subtle than open propaganda; it worked over the years by influencing what was taught, how it was taught, and what was “normal” in youth discussions.

2. How They Infiltrated

A. Recruitment & Placement

- Refugee movements & border connections allowed many Bengalis with India-friendly leanings to enter East Pakistan posing as teachers or lecturers.

- Indian agencies sponsored fellowships, training programs, and cross-border academic exchanges, through which selected individuals returned to East Pakistan with pro-Indian narratives.

- Some were already in East Pakistan’s education system but were cultivated by Indian handlers with incentives, ideology, or promises of future positions in an “independent Bangladesh.”

B. Targeted Levels of Education

- Primary & Secondary Schools

- Introduced subtle distortions in history lessons: overemphasis on Bengali cultural uniqueness, underplaying Islamic unity and the Pakistan Movement.

- Spread the idea that West Pakistan was culturally alien and economically exploitative.

- Colleges & Universities

- Planted lecturers and professors who encouraged secular Bengali nationalism over Islamic nationalism.

- Promoted literature and political thought from India-friendly Bengali writers.

- Used student discussion groups to normalise anti-West Pakistan rhetoric.

- Teacher Training Institutes

- Controlled future multipliers, training teachers to carry forward the same ideological slant in classrooms across rural and urban areas.

3. Methods of Brainwashing & Polarisation

A. Curriculum Manipulation

- Skewed historical narratives:

- Downplayed the role of West Pakistani leaders in independence from Britain.

- Amplified grievances like the Language Movement (1952) but framed them as deliberate oppression by West Pakistan.

- Introduced cultural pride narratives that subtly equated “Bengali culture” with India’s Bengal, rather than with the Muslim identity of Pakistan.

B. Covert Political Indoctrination

- Teachers aligned with the Indian policy encouraged participation in student political wings of the Awami League.

- Framed economic disparities as deliberate West Pakistani exploitation, ignoring complex economic realities.

C. Linking with Student Unions

- Universities like Dhaka University became hotbeds of nationalist activism.

- Student leaders were cultivated by faculty linked to Indian networks.

- Indian publications, political pamphlets, and underground newsletters circulated widely on campuses.

D. Cultural Programming

- School and college events increasingly promoted Tagore, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, and other Indian/Bengali icons, diluting emphasis on pan-Islamic or Pakistan-oriented symbols.

- Poetry, drama, and debates were used to glorify “Bengali freedom” narratives.

4. Why It Was Effective

- Youth were the most receptive to identity-based grievances.

- Classroom influence carried more credibility than overt political propaganda; if a respected professor said it, it felt true.

- East Pakistan already had some legitimate complaints about political marginalisation; Indian-sponsored educators amplified these into a narrative of inevitable separation.

- Universities and colleges became recruitment grounds for Mukti Bahini cadres in 1971.

5. The Link to 1971

- By the time Operation Searchlight began in March 1971, the mental groundwork had already been laid:

- A large segment of East Pakistan’s educated youth saw West Pakistan as an alien oppressor.

- Teachers and professors served as both ideological guides and logistical facilitators for students joining Mukti Bahini or engaging in sabotage.

- Many intellectual leaders of the Mukti Bahini movement were products of this pre-war academic indoctrination, deliberately nurtured by Indian influence.

The Pivotal 1970 General Elections: A Moment of Truth

In Pakistan’s Emergence and East Pakistan’s Struggle, the 1970 general elections were Pakistan’s first nationwide democratic elections and a watershed moment. The Awami League, under Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won an overwhelming majority in East Pakistan, securing 160 of 162 East Pakistani seats and thus a majority in the 300-seat National Assembly. This entitled them democratically to form the federal government.

However, West Pakistani leaders, especially Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the military regime under General Yahya Khan, refused to allow the transfer of power. Bhutto, lacking any seats in East Pakistan, rejected the Awami League’s mandate, while the military-authoritarian leadership stalled the process, fearing loss of control and national disintegration.

This political betrayal shattered faith in the Pakistani federation from East Pakistan’s perspective. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman called for a non-cooperation movement, effectively paralysing Pakistani government functions in the east and escalating demands from autonomy to full independence.

The Mukti Bahini (literally “Liberation Force”) was a Bengali guerrilla force active in 1971 during the Bangladesh Liberation War, which culminated in the breakup of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

Here’s the breakdown of what it was, who created it, and how it fit into the bigger Indian strategy.

1. What Was Mukti Bahini

- The Mukti Bahini was a Bengali nationalist militia formed primarily from defected East Pakistan soldiers, paramilitary forces, and civilian volunteers.

- It fought against the Pakistan Army in 1971 after the military crackdown in East Pakistan (Operation Searchlight, March 25, 1971).

- While initially an improvised local resistance, it soon became a well-organised insurgency heavily trained, armed, and directed by India.

2. Who Created It & Motives

Key Role of India

- India’s external intelligence agency, RAW (Research and Analysis Wing) and military leadership took the lead in organising the Mukti Bahini from April 1971 onward.

- Prime Minister Indira Gandhi approved Operation Jackpot, the codename for India’s covert aid to Bengali rebels.

- Indian motives:

- Weaken and break Pakistan by exploiting internal discontent in East Pakistan.

- Remove the two-front structure of Pakistan (East and West), which was strategically difficult for India.

- Support Bengali separatists to install a pro-India, friendly state on its eastern border.

Bengali Political Link

- The political umbrella was the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, which had won the 1970 elections in Pakistan.

- After West Pakistani political leadership refused to transfer power and the military crackdown began, many Awami League leaders fled to India, where they became the political leadership in exile for the Mukti Bahini.

3. Mukti Bahini’s Role in Dismemberment

- Guerrilla Warfare: Mukti Bahini fighters disrupted supply lines, attacked Pakistan Army convoys, and sabotaged communication networks in East Pakistan.

- Intelligence Gathering: Provided India with real-time military intelligence about Pakistani troop positions.

- Destabilisation: Kept the Pakistan Army engaged in multiple small battles, weakening their hold over the countryside.

- Psychological Impact: Propaganda operations (often with Indian media help) portrayed the Pakistan Army as an “occupation force” and fueled Bengali nationalism.

- Facilitating Indian Invasion: In December 1971, Mukti Bahini coordinated with the advancing Indian Army, guiding them through the terrain and targeting remaining Pakistani positions.

4. Other Means India Used Alongside Mukti Bahini

India’s campaign wasn’t just military; it was multi-dimensional, aimed at misguiding, brainwashing, and mobilising East Pakistani youth against West Pakistan:

A. Propaganda & Psychological Warfare

- Radio Free Bengal (Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra):

- Broadcast anti-Pakistan and pro-independence messages in Bengali.

- Spread exaggerated or fabricated stories of atrocities to inflame public anger.

- Film & Print Media:

- Indian and international journalists were shown curated scenes of “genocide” to sway world opinion.

- Posters, leaflets, and songs glorifying the Mukti Bahini circulated widely.

B. Political Grooming

- Awami League activists in India were given platforms, resources, and international connections to lobby for Bangladesh recognition.

- Youth leaders were encouraged to present the struggle as a freedom movement rather than a secession.

C. Training & Arms

- India set up more than a dozen training camps along its border with East Pakistan.

- RAW and Indian military instructors trained over 100,000 guerrillas in sabotage, ambush, and intelligence work.

D. Diplomatic Pressure

- India lobbied in the UN and major capitals to portray Pakistan as a violator of human rights.

- Garnered Soviet support through the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship (Aug 1971), giving India strategic backing.

E. Infiltration & Espionage

- Indian operatives disguised as refugees crossed into East Pakistan to link up with local youth and organize underground cells.

- Local Bengali police, civil servants, and students were encouraged to defect or pass information.

5. Outcome

- The combination of internal unrest, Mukti Bahini guerrilla operations, Indian propaganda, and eventual direct military intervention overwhelmed Pakistani defences.

- On December 16, 1971, Pakistan’s Eastern Command surrendered to the combined Indian Army and Mukti Bahini forces.

- Bangladesh emerged as an independent state, with deep Indian influence in its early years.

Military Rule and Escalation of Tensions

Martial law, first imposed by General Ayub Khan in 1958 and later carried on by General Yahya Khan, entrenched a militarised approach to governance, sidelining civilian political processes.

The military government’s refusal to acknowledge election results, combined with repressive measures—censorship, banning political parties, arrests of leaders including Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—turned political unrest into open rebellion.

This tension culminated in Operation Searchlight in March 1971, a brutal military crackdown targeting political activists, intellectuals, and civilians, sparking a full-scale liberation war.

The Road to the Birth of Bangladesh

The refusal of West Pakistan’s ruling elite to accommodate East Pakistan’s democratic mandate and legitimate aspirations, the military’s use of force, and India’s covert and overt support for independence fighters transformed Pakistan’s political crisis into a bloody civil war.

East Pakistani military units defected to form the Bangladesh Forces, and millions of refugees flooded into India, prompting Indian military intervention in December 1971.

After a nine-month war, the fall of Dhaka and the surrender of Pakistani forces marked Bangladesh’s emergence as an independent nation on December 16, 1971.

Reflections on Lessons Learned

The emergence and eventual fracturing of Pakistan stand as a potent reminder of the complexities in nation-building across diverse regions. The leadership’s inability to foster inclusive political participation, equitable economic development, and cultural respect sowed seeds of division.

External interference compounded internal fissures, while democratic denial and military repression escalated tensions beyond repair.

For contemporary readers and policymakers, Pakistan’s Emergence and East Pakistan’s Struggle, this history underscores the imperative of fair governance, respect for political mandates, accommodation of diversity, and recognition of popular aspirations as the pillars of national unity.

References

-

“East Pakistan,” Wikipedia, accessed August 2025.

-

“The Breakup of Pakistan 1969-1971,” Dawn Special Report, December 2024.

-

“1970 Pakistani General Elections,” Scribd, May 2025.

-

“1970 Pakistani general election,” Wikipedia, January 2007.

-

“When an election broke Pakistan in two,” India Today, February 2024.

-

UCA.edu Political Science Project on Pakistan/East Pakistan/Bangladesh (1947-1971), 2018.

This article traces the sweeping journey from Pakistan’s emergence, through East Pakistan’s pivotal struggles led by visionary leaders, the missteps of early governance, to the climactic battle that gave birth to Bangladesh. It captures a nuanced history reflecting political ambitions, human resilience, and a cautionary tale on the consequences of division within a nation.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Pakistan

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1359141

- https://www.indiatoday.in/history-of-it/story/pakistan-election-2024-national-assembly-polls-1970-yahya-khan-sheikh-mujibur-rahman-zulfikhar-ali-bhutto-imran-khan-2499656-2024-02-09

- https://www.scribd.com/document/441389089/1970-Pakistani-general-elections

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1970_Pakistani_general_election

- https://uca.edu/politicalscience/home/research-projects/dadm-project/asiapacific-region/pakistanbangladesh-1947-1971/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWUKeud3PPw

- https://philarchive.org/archive/IQBPOS

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/list-of-prime-ministers-of-Pakistan-2230533