The Great Depression of the 1930s: A Global Economic Catastrophe and Its Resolution

The Great Depression of the 1930s is the most severe and prolonged economic downturn in modern history, lasting nearly a decade from late 1929 until about 1939. Far more devastating than any recession before or since, this financial collapse fundamentally transformed societies, governments, and economic systems worldwide. What began as a stock market crash in the United States rapidly evolved into a global catastrophe that left millions unemployed, homeless, and desperate for relief.

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and business failures around the world. The economic contagion began in 1929 in the United States, the largest economy in the world, with the devastating Wall Street stock market crash of October 1929 often considered the beginning of the Depression. Among the countries with the most unemployed were the U.S., the United Kingdom, and Germany.

The Perfect Storm: Factors Leading to The Great Depression of the 1930s

The Roaring Twenties and the Inevitable Crash

The 1920s, often called the “Roaring Twenties,” witnessed unprecedented economic expansion in the United States. Stock prices soared to dizzying heights as ordinary Americans, captivated by the prospect of easy wealth, poured their savings into the market. Many even mortgaged their homes to purchase stocks, believing prices would rise indefinitely. By the end of the decade, hundreds of millions of shares were being purchased on margin – bought with loans that investors planned to repay with profits from ever-increasing share prices[1].

This speculative bubble was destined to burst. When prices began declining in October 1929, panic ensued. Overextended shareholders rushed to liquidate their holdings, causing stock prices to plummet. Between September and November 1929, stock prices fell by a staggering 33 percent[1]. This crash wasn’t merely a financial setback – it delivered a profound psychological shock that shattered consumer and business confidence alike.

Tom Wilson, a former New York banker, recalled: “The day the market crashed, you could hear a pin drop on Wall Street. Men who had been millionaires on paper stood in shocked silence as their fortunes evaporated before their eyes. One of my clients lost everything and walked straight from the trading floor to the Brooklyn Bridge. He wasn’t the only one.”

Banking System Failures and Financial Panics

As the depression deepened, weaknesses in the banking system became painfully apparent. Starting in October 1930, rural banks began failing as farmers defaulted on loans[4]. The United States lacked federal deposit insurance at this time – bank failures were considered a normal, if unfortunate, part of economic life. As news of bank closures spread, worried depositors rushed to withdraw their savings, creating a destructive cycle. When too many customers demanded their money simultaneously, banks had to liquidate assets by calling in loans rather than creating new ones[4].

This devastating domino effect caused the money supply to shrink dramatically and the economy to contract in what economists later called the “Great Contraction.” With fewer dollars in circulation, price deflation increased, putting additional pressure on already struggling businesses[4].

The Golden Handcuffs: Monetary Policy Restrictions

The international gold standard, which linked nearly all the world’s major economies in a network of fixed currency exchange rates, played a crucial role in transmitting America’s economic crisis globally[2]. Under this system, governments maintained fixed exchange rates between their currencies and gold.

The U.S. government’s commitment to the gold standard severely restricted its ability to implement expansionary monetary policy that might have cushioned the economic fall. To maintain gold reserves and attract international investors, the United States kept interest rates high, which discouraged domestic business borrowing and investment precisely when stimulation was desperately needed[4].

France’s decision to raise its interest rates to attract gold further complicated America’s situation. With limited options under the gold standard, the U.S. had to maintain high interest rates to prevent gold outflows, inadvertently deepening the depression[4].

International Debt Structure After World War I

The Great Depression’s seeds were partially sown in the aftermath of World War I, which had profoundly disrupted international power balances and financial systems[5]. The war’s enormous costs forced many nations to temporarily abandon the gold standard. Though countries worked diligently to restore it by decade’s end, this reestablishment introduced dangerous inflexibility into domestic and international financial markets[5].

The post-war debt structure created precarious dependencies. European nations, struggling to rebuild after the war, relied heavily on American loans. When the U.S. economy collapsed in 1929, loan availability dried up, sending economic shockwaves across the Atlantic. This interconnected debt structure ensured that economic distress in one major economy would quickly spread to others.

Global Reach: Nations That Contributed to the Depression’s Severity

The United States: Ground Zero

The United States, as the world’s emerging economic superpower, played a central role in both causing and deepening the Great Depression. American financial policies and economic decisions had ripple effects worldwide. The nation’s adoption of protectionist trade policies, particularly the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, drastically reduced international trade at the worst possible moment[4].

This tariff raised import duties to protect American producers but prompted retaliatory measures from trading partners, causing global trade to collapse. As international commerce withered, economies worldwide suffered additional damage, illustrating how well-intentioned but misguided policies can amplify economic crises.

European Powers: Fragile Economies in Transition

Great Britain, which had long served as the global financial system’s anchor, found itself unable to play its traditional leadership role as it struggled with its own economic difficulties[5]. Having experienced low growth and recession during most of the late 1920s, Britain slipped into severe depression in early 1930[2]. Though its industrial production declined less dramatically than America’s (approximately one-third of the U.S. drop), Britain’s weakened position left a leadership vacuum in international economic coordination.

Germany, still recovering from World War I and burdened by reparation payments, experienced an economic downturn beginning in early 1928. After briefly stabilizing, it turned downward again in late 1929, ultimately suffering industrial production declines roughly equal to those in the United States[2]. The severe economic conditions in Germany had fateful political consequences, contributing to Hitler’s rise to power.

France initially weathered the storm better than many nations, experiencing a relatively short downturn in the early 1930s. However, this recovery proved temporary. Between 1933 and 1936, French industrial production and prices fell substantially, indicating the crisis had merely been delayed rather than avoided[2].

The Gold Standard: A Transmission Mechanism for Economic Disaster

Perhaps the most significant contributor to the Depression’s global severity wasn’t a country but a system – the international gold standard. This monetary system, which had functioned relatively well before World War I, became a mechanism for transmitting economic distress between nations[3].

Under the gold standard, countries experiencing economic difficulties couldn’t easily implement monetary policies to stimulate growth. Instead, they were forced to maintain high interest rates to prevent gold outflows, essentially prioritizing currency stability over domestic economic health. This rigid system prevented the flexibility needed to respond to economic crises effectively.

The Human Cost: Nations Most Severely Affected

United States: Unprecedented Suffering

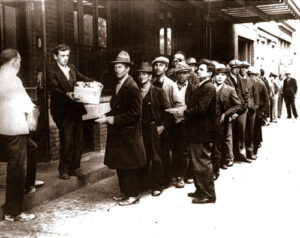

The United States experienced the Depression’s most devastating effects. Between 1929 and 1933, industrial production plummeted nearly 47 percent, gross domestic product declined by 30 percent, and unemployment soared to more than 20 percent of the workforce[1]. For perspective, during the 2007-2009 Great Recession (the second-largest economic downturn in U.S. history), GDP declined by just 4.3 percent, and unemployment peaked at less than 10 percent[1].

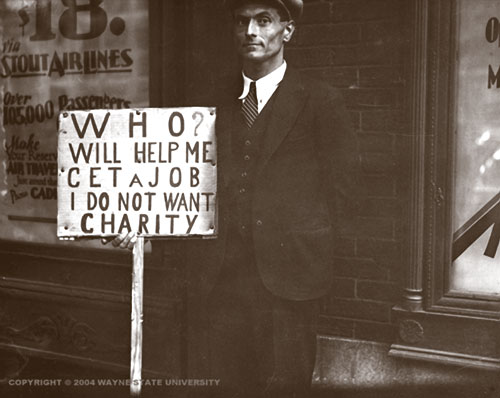

These statistics, while shocking, fail to capture the human suffering. Millions of Americans lost their homes, farms, and businesses. Homeless encampments called “Hoovervilles” (named bitterly after President Herbert Hoover) sprang up nationwide. Families were separated as men traveled the country seeking work. Hunger became commonplace in what had been the world’s wealthiest nation.

Sarah Johnson, who grew up in Oklahoma during the Depression, later recalled: “We didn’t know we were poor because everyone around us was in the same boat. My father worked whenever he could find anything – picking cotton, digging ditches, whatever paid something. Some days, we had nothing but cornbread to eat. My mother would skip meals, claiming she wasn’t hungry, but I knew she was giving us her portion.”

Germany: Economic Disaster with Political Consequences

Germany’s experience with the Depression proved particularly consequential for world history. Already struggling with war reparations and hyperinflation in the 1920s, Germany could ill afford another economic catastrophe. As unemployment skyrocketed and businesses failed, political extremism gained traction. Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party skillfully exploited economic grievances, presenting itself as the solution to Germany’s problems.

The connection between economic desperation and political radicalization in Germany offers a sobering lesson about how economic conditions can shape political outcomes. While most countries experiencing depression maintained their political systems despite enormous stress, Germany’s fragile democracy collapsed, with catastrophic consequences.

Global Variations in Severity

While industrialized Western nations generally suffered most severely, the Depression’s impact varied considerably worldwide. Japan experienced a relatively mild depression that began later and ended earlier than in Western countries[2].

Latin American nations showed significant variation in their experiences. Argentina and Brazil weathered comparatively mild downturns, while other countries in the region plunged into severe depressions[2]. Some less-developed countries, less integrated into the global financial system, actually experienced less severe effects than more industrialized economies.

The timing also varied substantially across countries. Some Latin American nations began experiencing downturns in late 1928 and early 1929, before the U.S. decline began[2]. This timing variation reminds us that while the Great Depression was indeed a global phenomenon, it manifested differently across regions and economies.

Fighting Back: The Great Depression of the 1930s, How Nations Confronted the Crisis

Initial Responses and Their Inadequacy

Early responses to the Depression reflected traditional economic thinking that proved woefully inadequate for a crisis of this magnitude. Many governments initially responded with policies designed to balance budgets, maintain the gold standard, and allow markets to correct themselves with minimal intervention.

President Herbert Hoover, though more active than sometimes portrayed, resisted direct federal relief efforts and large-scale government intervention. His administration established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide emergency loans to banks and businesses, but stopped short of direct aid to individuals. These limited measures proved insufficient against the Depression’s overwhelming force.

The New Deal: America’s Bold Experiment

With Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election in 1932, American policy shifted dramatically. Roosevelt’s New Deal represented an unprecedented expansion of the government’s role in economic affairs. His administration implemented banking reforms, agricultural price supports, massive public works projects, and new social programs like unemployment insurance and Social Security[3].

The National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act of 1935 encouraged collective bargaining, contributing to a doubling of union membership between 1930 and 1940[3]. The Social Security Act of 1935 established unemployment compensation and old-age and survivors’ insurance in response to the Depression’s hardships[3].

While historians debate the New Deal’s economic effectiveness, its psychological impact was undeniable. Roosevelt’s confident leadership and willingness to experiment with new approaches restored hope to a demoralized nation. His famous first inaugural address, asserting that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” marked a turning point in public sentiment.

Abandoning Gold: Monetary Freedom

Perhaps the most significant policy change worldwide was the abandonment of the gold standard, which freed countries to pursue expansionary monetary policies. Great Britain left the gold standard in 1931, and the United States followed in 1933. Other countries soon made similar moves[3].

This shift represented a fundamental change in economic thinking. While many economists and policymakers had viewed the gold standard as essential to economic stability, the Depression revealed its potential to amplify economic disasters. Without the constraints of fixed exchange rates, countries could devalue their currencies, lower interest rates, and increase money supplies to stimulate their economies.

Step-by-Step Guide: How Countries Recovered from the Depression

For readers interested in understanding how nations navigated their way out of the Depression, here’s a simplified step-by-step guide to the recovery process:

1. Abandonment of orthodox policies: Countries that recovered most quickly typically abandoned traditional approaches first (balanced budgets, gold standard, limited government intervention).

2. Currency devaluation: After leaving the gold standard, many countries devalued their currencies, making exports more competitive and stimulating production.

3. Monetary expansion: Central banks in Countries implemented banking regulations and deposit insurance to restore confidence in financial institutions.

6. Social safety nets: New programs providing unemployment insurance, old-age benefits, and other protections helped maintain consumption levels and social stability.

7. Industrial and agricultural policies: Various initiatives aimed at specific sectors helped address overproduction, price collapses, and structural problems.

8. Trade policy adjustments: After the failure of protectionism, many countries gradually moved toward more balanced trade policies.

9. Rearmament: As geopolitical tensions increased in the late 1930s, military spending provided additional economic stimulus.

10. Wartime mobilization: World War II ultimately ended the Depression through massive government spending, full employment, and industrial expansion.

Recovery and Lasting Legacy

Uneven and Incomplete Recovery

Economic improvement began at different times in different countries, but was generally underway by the mid-1930s. However, the recovery proved uneven and incomplete. In the United States, a serious recession in 1937-1938 temporarily reversed progress when the government prematurely reduced spending and tightened monetary policy[4]. While conditions improved compared to the Depression’s depths, full recovery remained elusive.

True recovery came only with the onset of World War II, which created enormous demand for goods and labor. The massive government spending and industrial mobilization required by the war finally ended the Depression conclusively, though at the terrible cost of global conflict.

Transformative Economic Changes

The Great Depression permanently altered economic systems and thinking worldwide. The welfare state expanded substantially in many countries[3]. After experiencing the Depression’s devastating effects, many nations established or strengthened social safety nets designed to prevent comparable suffering in future downturns.

International economic coordination also changed fundamentally. While the immediate response to the Depression featured increased nationalism and protectionism, the post-World War II economic order reflected lessons learned from these mistakes. The Bretton Woods system, established after the war, created new international financial institutions and a modified fixed exchange rate system with greater flexibility than the gold standard[3].

Psychological and Cultural Impact

Perhaps the Depression’s most enduring legacy was psychological. A generation that experienced severe economic deprivation developed lasting habits of frugality, risk aversion, and financial caution. Families who lived through the 1930s often continued saving string, reusing items, and maintaining emergency supplies long after prosperity returned.

The Depression also transformed perspectives on the government’s proper role, particularly in the United States. Before 1929, limited government intervention in economic affairs was the norm. Afterward, most Americans expected the government to take active measures to prevent economic disasters and provide basic social protections.

Conclusion: Lessons for Today

The Great Depression offers essential lessons that remain relevant for contemporary economic challenges. First, it demonstrates how interconnected the global economy has always been – problems in one major nation inevitably affect others. Second, it illustrates the dangers of dogmatic adherence to economic orthodoxies when circumstances require flexibility. The gold standard, once considered essential to prosperity, became a transmission mechanism for economic disaster.

Most importantly, the Depression reminds us that economic statistics represent real human lives. Behind every percentage of unemployment or GDP decline lie countless personal stories of hardship, adaptation, and resilience. Understanding Depression requires acknowledging both its economic dimensions and its profound human impact.

As we face our economic challenges in the 21st century, the Great Depression stands as both a warning and guide – a reminder of our economic systems’ vulnerabilities and the importance of decisive, coordinated responses to financial crises. By studying this pivotal historical event, we gain insights that can help prevent comparable suffering in our own time.

Citations:

[1] https://www.britannica.com/story/causes-of-the-great-depression

[2] https://www.britannica.com/money/topic/Great-Depression

[3] https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Depression/Economic-impact

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression_in_the_United_States

[5] https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/great-depression

[6] https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/rise-to-world-power/great-depression/a/the-great-depression

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression

[8] https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/overview/

[9] https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/americans-react-to-great-depression/

[10] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-great-depression

[11] https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-worldcivilization2-1/chapter/the-great-depression/

[12] https://academic.oup.com/oxrep/article/26/3/285/374047?login=false

[13] https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-depression

[14] https://courses.lumenlearning.com/tc3-boundless-worldhistory/chapter/the-great-depression/

[15] https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Depression/Causes-of-the-decline

[16] https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fmcc-boundless-worldhistory/chapter/the-great-depression/

[17] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/great_depression.asp

[18] https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Depression

[19] https://www.britannica.com/event/stock-market-crash-of-1929

[20] https://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/past-recessions.asp