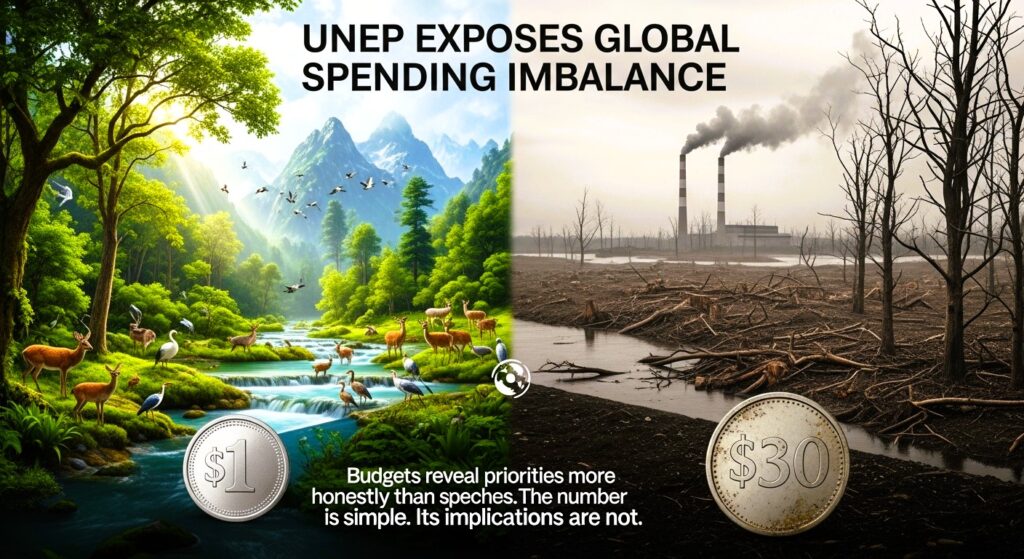

$1 to Save Nature, $30 to Destroy It: UNEP Exposes Global Spending Imbalance

$1 to Save Nature, $30 to Destroy It. For every one dollar the world spends on protecting nature, it spends thirty dollars damaging it.

This conclusion comes from the latest analysis by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the UN’s principal authority on environmental assessment.

Budgets speak louder than climate promises; this is what world leaders are really funding.

The number is simple.

Its implications are not.

https://mrpo.pk/air-pollution-the-elephant-in-the-room/

While governments continue to issue climate pledges and biodiversity commitments, public budgets and financial systems remain heavily tilted toward activities that degrade ecosystems, accelerate climate risks, and weaken long-term resilience. The gap between ambition and action, UNEP suggests, is no longer marginal; it is systemic.

More money is spent on destroying nature and less on protecting it

For every dollar we spend on saving nature, we spend more than $30 on destroying it, according to a new report from the UN environmental agency UNEP.

In 2023, $7.4 trillion was spent on activities that harm nature, such as industry, fossil fuels, and agriculture. Most of it came from the private sector.

Of the $220 billion invested in protecting and restoring nature, just over ten percent came from private sources.

“If you follow the money, you see the scale of the challenge that lies ahead,” said UNEP Director Inger Andersen in a press release.

UNEP estimates that investments in nature-based solutions must increase to $572 billion per year by 2030 to meet the agreed global goals.

https://swedenherald.com/article/more-money-spent-on-destroying-nature-and-less-on-protecting-it

What the UNEP Report Shows

UNEP’s State of Finance for Nature assessment finds that global finance overwhelmingly favours nature-negative activities, including:

- Fossil fuel production and consumption

- Environmentally harmful agricultural subsidies

- Mining and extractive industries

- Infrastructure linked to deforestation and habitat loss

By contrast, nature-positive investments such as ecosystem restoration, conservation, and sustainable land use receive a small fraction of total spending.

UNEP’s core finding is carefully worded but unmistakable:

Current financial flows are misaligned with global environmental goals.

Power and Responsibility Are Concentrated

Environmental damage affects everyone, but responsibility is not evenly shared.

The Five Veto Powers and Global Influence

The five permanent members of the UN Security Council—the United States, China, Russia, the United Kingdom, and France hold unmatched political and economic leverage. Collectively, they:

- Contribute a significant share of global emissions

- Dominate fossil fuel production, trade, and finance

- Influence international development and security decisions

- Possess veto authority over binding global action

Suggested infographic:

Share of global emissions and environmentally harmful subsidies vs. share of nature-protection finance among the five veto powers.

UNEP data indicate that despite their capacity to lead, environmentally harmful spending within and linked to these economies continues to exceed investment in nature protection by a wide margin.

High-Income Nations: Progress Alongside Contradiction

Wealthier and highly educated economies—primarily within the OECD and G7—have introduced carbon pricing, renewable energy incentives, and environmental regulations. These efforts matter and have delivered measurable gains.

At the same time, these countries:

- Account for a disproportionate share of historical emissions

- Maintain high levels of resource and energy consumption

- Drive environmental degradation abroad through global supply chains

The contradiction lies not in intent, but in scale.

Incremental reforms coexist with large, persistent subsidies that undermine them.

Countries Linked to Major Environmental Pressures (By Category)

UNEP and related international data point to sector-based responsibility, rather than uniform blame.

Climate and Emissions

- Large industrial and manufacturing economies

- Fossil fuel-dependent energy systems

Deforestation and Biodiversity Loss

- Agricultural expansion

- Mining and transport infrastructure

- Consumption-driven global demand

Plastic Pollution and Marine Degradation

- Major producers of plastic waste

- Industrial fishing fleets

- Export of waste to lower-income countries

Suggested map graphic:

Environmental damage hotspots compared with global consumption centres.

Who Bears the Consequences

Countries least responsible for environmental degradation often experience the most severe impacts, floods, heatwaves, food insecurity, water stress, and displacement.

Suggested comparison table:

| Indicator | High-Emitting Countries | Vulnerable Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Contribution to emissions | High | Low |

| Climate impacts | Manageable | Severe |

| Recovery capacity | Strong | Limited |

This imbalance underscores that environmental degradation is also a matter of equity and resilience.

Following the Money: Why the $30 Persists

UNEP identifies several structural drivers behind continued nature-negative spending:

- Subsidies that lower the cost of environmentally harmful activities

- Public finance and export credit support for extractive industries

- Investment frameworks prioritising short-term economic returns

These flows are legal, normalised, and deeply embedded in existing economic systems.

Where Progress Is Real

Balanced assessment requires acknowledging genuine advances.

Across regions, governments have demonstrated practical environmental capacity, including:

- Rapid expansion of renewable energy

- Reforestation and ecosystem restoration programs

- Urban transport and efficiency reforms

- Stronger environmental regulatory frameworks

The European Union, China, the United States, and Nordic countries each provide examples of policies that align with UNEP’s recommended pathways.

UNEP cautions, however, that these gains remain outpaced by harmful financial flows, limiting their net effect.

A Case Study From the Global South: Pakistan’s Restoration Efforts

Environmental action is often framed as a privilege of wealth. Yet UNEP’s analysis repeatedly highlights ecosystem restoration in developing countries as one of the most cost-effective climate and biodiversity strategies.

Pakistan offers a relevant example.

During the period when Imran Khan served as Prime Minister, Pakistan expanded large-scale afforestation and land-restoration initiatives, building on earlier provincial efforts. These included:

- The Billion Tree Tsunami project

- The nationally scaled Ten Billion Tree Tsunami Programme

The programs focused on:

- Reforestation and mangrove restoration

- Ecosystem rehabilitation

- Climate resilience and employment generation

UNEP’s finance assessments emphasise that nature-based solutions such as reforestation and ecosystem restoration deliver high environmental and social returns relative to cost, particularly in climate-vulnerable regions. The report also notes that restoration in developing countries can generate disproportionate global benefits when sustained and properly financed.

Pakistan’s experience illustrates a broader UNEP finding:

technical capacity exists across income levels; the main constraint is financial alignment and continuity.

At the same time, UNEP stresses that isolated national efforts show effectiveness, but cannot compensate for a global system that continues to prioritise environmentally harmful spending elsewhere.

The Central Issue: Ratios, Not Rhetoric

Environmental leadership is ultimately reflected in budgetary choices.

As long as governments collectively spend thirty times more on activities that degrade nature than on those that protect it, progress will remain incremental and fragile.

The issue, UNEP makes clear, is not the absence of solutions—but the persistence of misaligned incentives.

What UNEP Recommends

UNEP calls for:

- Phasing out environmentally harmful subsidies

- Redirecting existing finance toward nature-positive outcomes

- Aligning economic planning with ecological limits

- Treating ecosystem protection as a core economic priority

These recommendations focus on redirection, not economic disruption.

Conclusion

The UNEP report does not describe a universal failure. It reveals a concentrated one, rooted in policy and financial choices made by those with the greatest influence over global systems.

The $1-to-$30 imbalance is more than a statistic.

It is a measure of priorities.

Correcting it is not a question of knowledge or capability.

It is a question of will.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does the $1 vs. $30 ratio mean?

It compares global spending on nature protection with spending that harms ecosystems.

2. Who published this analysis?

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

3. Are all countries equally responsible?

No. Environmental impact and financial influence are highly concentrated.

4. Does UNEP recognise positive environmental action?

Yes, but it notes these efforts are outweighed by harmful financial flows.

5. Why does harmful spending continue?

Because subsidies, political pressures, and short-term economic priorities persist.

6. Can the imbalance be corrected?

Yes, primarily by redirecting existing finance.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), State of Finance for Nature

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

- OECD Environmental Indicators

- World Bank Climate and Environment Data